The Argument for Emergent Language Models

Human-Like Language Cognition Will Emerge From Multi-Agent Interaction

Language is a defining feature of human intelligence. Its power lies not merely in our ability to comprehend it, but to learn it with sparse supervision, to leverage it to make decisions, and to invent symbols for new and useful meanings. The central shortcoming of today’s language models is that they truly are not complete models of language. A complete computational model of human language capability must in fact account for the full gamut of linguistic competence—not just understanding existing language, but acquiring it from experience and inventing it in new situations. Building models that span these abilities would yield enormous explanatory power for the study of human cognition and, I believe, are essential for developing AI systems that can truly grasp language. Throughout my doctoral studies, I have dedicated my research to this goal: constructing computational models of grounded language that integrate insights from linguistics, cognitive science, and AI. I’ve written this post to explain my research agenda as I finish my doctoral studies and pursue postdoctoral research.

Language Is About the World

The main thesis motivating my work is that language was invented by humans to reason about and describe their subjective experience of the world. That world is defined by rich sensory perception, internal reasoning, and motor action mediated and generated by the brain. Humans ultimately are embodied decision-makers, and the utility of language is derived from our ability to leverage it to make fruitful decisions in the world. To achieve this, we must ultimately render language in terms of perception and action—the machinery of decision-making. At a high level, my entire research agenda is about how to achieve this rendering.

The first foundational assumption I made during my PhD is that the Markov Decision-Process and its structured and partially-observable variants (Puterman, 1990; Diuk et al., 2008; Masson et al., 2016; Kaelbling et al., 1998; Oliehoek, 2012) are sufficiently expressive representations of the world of human decision-making—or perhaps a good starting point. For one, structured MDPs inadvertently contain many of the same perception and action structures that humans have (e.g. objects, lifted skills) and also that language has (e.g. nouns, verbs; Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2020). Structured MDPs are also a useful analog for human decision-making thanks to decades of research on solving them using planning and reinforcement learning (Sutton and Barto, 1998), and on learning structured MDPs from structureless observation and action (Sutton et al., 1998; Konidaris et al., 2018; Allen et al., 2021).

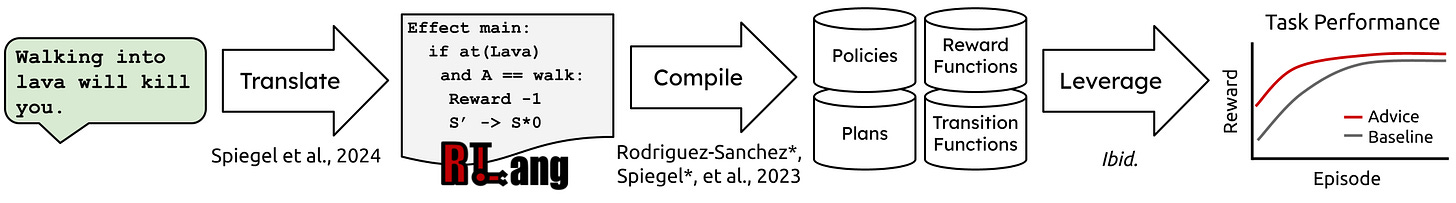

What follows is that the meaning of language should be represented in terms that ground to structured decision-making. My first crack at this was to develop a semantic logical form for natural language that compiles into statements about structured MDPs and their solutions (Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2023)1, and then to translate natural language into this logical form using large language models (Spiegel et al., 2024). By grounding the meaning of language to decision-theoretic terms, I was able to demonstrate how a wide variety of language advice could be understood natively by a learning agent, extending the semantics of language to decision-making.

We Should Evolve Language Models

The RLang approach was a successful proof-of-concept for grounding language to decision-making, but it carried the same practical difficulties faced by classical linguists in their accounts of meaning: such models are useful insofar as humans can prescribe their semantics2. Hand-specifying the entirety of language semantics in decision-theoretic terms is intractable—it would require solving the same problems that classical semanticists struggled with and more3. The Bitter Lesson that the field has learned over the past decade is that we should abandon the prescription of solutions in favor of methods that learn solutions from data. So I instead began a new direction that explores the conditions by which artificial agents will invent human-like languages about their environment.

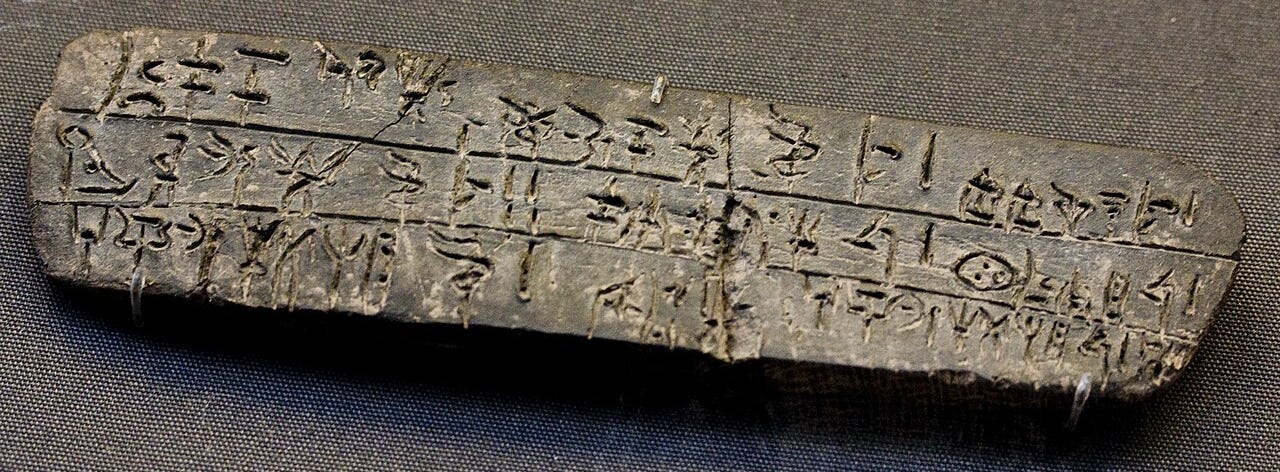

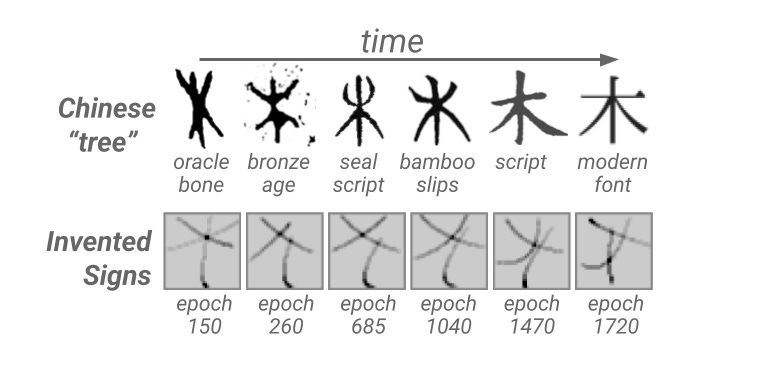

In contrast to the supervised approaches of VLMs and VLAs, which rely on joint-embedding, auto-regressive prediction, or diffusing tuples of language and multi-modal data, my approach instead treats language as an emergent phenomena that arises from grounded interaction with other agents in a decision-process. In my recent work on the cognitive and cultural preconditions for symbolic signaling (Spiegel et al., 2025), I show that a Bayesian “visual theory of mind” is sufficient for bootstrapping inferential communication between learning agents. By simulating millions of signaling interactions in a novel JAX-based signaling game, I demonstrated that agents will spontaneously invent proto-writing systems about their environment that evolve from iconic pictographs into abstract symbols—mirroring the trajectory of many human scripts (pictured top of post, below).

Over the next few years I will use emergent communication to model a broader range of linguistic phenomena across two axes: form and meaning. Can we recover the cognition that generates languages with human-like form, e.g. with morphophonological structure and compositional syntax? Likewise, can we build models that generate meanings about facets of the environment that humans would similarly invent language to describe? By adjusting the complexity of the environment, the partial observability of agent interactions, and the cognitive capabilities of the agents, I hypothesize we can evolve artificial languages that match the depth of human language while simultaneously getting at the core cognition behind language understanding, invention, and acquisition. Eventually, these models will lead to AI systems that can actually grasp language at the human level.

Why This Is More Bitter-Lesson-Pilled Than the Multimodal Approach

The chief problem with LLMs, VLMs, and VLAs is that they are synchronic models of present-day language that are explicitly supervised at the syntactic and semantic levels, preventing them from learning a robust method for acquiring new semantic concepts from experience. The multi-modal training paradigm asks a model to learn the semantics and the syntax of a language at the same time—supplying them with raw data and asking them to invent everything between the stimuli and the symbol4. Aside from violating intuition about how humans learn language, this paradigm sets an inherent limit on the language—and its entangled concepts—that these models can understand. We should instead be able to deploy agents in environments and watch them learn relevant and necessary concepts—and the signs for them—without supervision. If your system can’t acquire a new language efficiently, you haven’t solved language. If your system can’t invent a language about a new substrate, you haven’t solved language.

The wisdom behind the predict-next-token objective is that it contains within it the true desired task of language-learning—albeit with limited grounding, read my critique—without directly supervising its meaning. Similarly, I suggest we create languages via a broader optimization problem: maximizing return in a multi-agent decision-process requiring communication. If your goal is to capture the phenomena of language, you shouldn’t stop at English or Gaelic or Persian; the most Bitter-Lesson approach is to design a training regime that causes English and Gaelic and Persian to emerge from experience and interaction. Unless there are truly spooky factors at play in human language cognition, we should be able to simulate the cognitive and cultural circumstances in which human-like languages emerged. These languages lie on a manifold of natural languages that we can approach under the right experimental conditions. Once we get close enough, we’ll be able to translate agent-invented artificial languages into natural ones like English, Gaelic, Persian, etc. We could realistically do this in the next 10 years.

Why Hasn’t Emergent Communication Research Yielded These Results in the Past?

In short, we quit too early! There was some incredible research on emergent communication happening in the late twenty-teens and early twenties, especially by Serhii Havrylov, Mycal Tucker, Angeliki Lazaridou, Rahma Chaabouni, and Paul Michel5 (Lazaridou et al., 2017; Havrilov and Titov, 2017; Chaabouni et al., 2020; Michel et al., 2023; Tucker et al., 2025)—the last four have since shifted their work to LLMs. The biggest problem with the works of this era is that they rely on a limited class of signaling games (Lewis, 2008; Skyrms, 2010) that represent an oversimplified communication scenario where the signs and referents of language already exist. However, the very question of how signs and referents emerge is a crucial part of the language problem. To address these limitations, I designed a more general signaling game called a Signification Game that fits naturally into a broader class of decision-processes: multi-agent POMDPs. These Signification Games can gradually be extended to match the complexity of real-world human perception and action, and solving them will be skin to inventing human-like language. Under the right conditions, I believe this approach has the potential to yield artificial languages that rival the depth and expressivity of natural ones.

I’ll be wrapping up my PhD at Brown within the next year or so and I’m actively pursuing postdoctoral positions (and summer research internships) to continue this work. If this research interests you or your university/org, you can email me at bspiegel [at] cs [dot] brown [dot] edu. My website.

Works Cited

~excuse inconsistent citation style~

Allen, Cameron, et al. “Learning markov state abstractions for deep reinforcement learning.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (2021): 8229-8241.

B.A. Spiegel, L. Gelfond, G.D. Konidaris. Visual Theory of Mind Enables the Invention of Proto-Writing. Proceedings of the 47th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, July 2025.

R. Rodriguez-Sanchez*, B.A. Spiegel*, J. Wang, R. Patel, G.D. Konidaris, and S. Tellex. RLang: A Declarative Language for Describing Partial World Knowledge to Reinforcement Learning Agents. In Proceedings of the Fortieth International Conference on Machine Learning, July 2023.

B.A. Spiegel, Z. Yang, W. Jurayj, K. Ta, S. Tellex, and G.D. Konidaris. Informing Reinforcement Learning Agents by Grounding Natural Language to Markov Decision Processes, in Workshop on Training Agents with Foundation Models at RLC, August 2024.

Chaabouni, Rahma, Eugene, Kharitonov, Diane, Bouchacourt, Emmanuel, Dupoux, Marco, Baroni. “Compositionality and Generalization In Emergent Languages.” Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020.

Diuk, Carlos, Andre, Cohen, Michael L., Littman. “An object-oriented representation for efficient reinforcement learning.” Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Machine Learning. Association for Computing Machinery, 2008.

Havrylov, Serhii and Ivan Titov. “Emergence of Language with Multi-agent Games: Learning to Communicate with Sequences of Symbols.” Neural Information Processing Systems (2017).

Kaelbling, Leslie Pack, Michael L. Littman, Anthony R. Cassandra. “Planning and acting in partially observable stochastic domains”. Artificial Intelligence 101. 1(1998): 99-134.

Konidaris, George Dimitri et al. “From Skills to Symbols: Learning Symbolic Representations for Abstract High-Level Planning.” J. Artif. Intell. Res. 61 (2018): 215-289.

Lazaridou, Angeliki, Alexander Peysakhovich, and Marco Baroni. “Multi-Agent Cooperation and the Emergence of (Natural) Language.” International Conference on Learning Representations. 2017.

Lewis, David. Convention: A Philosophical Study. Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

Masson, Warwick, et al. “Reinforcement Learning with Parameterized Actions.” Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 30, no. 1, 21 Feb. 2016.

Michel, Paul et al. “Revisiting Populations in multi-agent Communication.” International Conference on Learning Representations (2023).

Mycal Tucker, Julie Shah, Roger Levy, Noga Zaslavsky; Towards Human-Like Emergent Communication via Utility, Informativeness, and Complexity. Open Mind 2025; 9 418–451.

Oliehoek, F.A. (2012). Decentralized POMDPs. In: Wiering, M., van Otterlo, M. (eds) Reinforcement Learning. Adaptation, Learning, and Optimization, vol 12. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Puterman, Martin L.. “Chapter 8 Markov decision processes.” (1990).

Rodríguez-Sánchez, Rafael et al. “On the Relationship Between Structure in Natural Language and Models of Sequential Decision Processes.” (2020).

R. S. Sutton and A. G. Barto, “Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction,” in IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 1054-1054, Sept. 1998.

R. S. Sutton, D. Precup, and S. Singh. 1998. Between MOPs and Semi-MOP: Learning, Planning & Representing Knowledge at Multiple Temporal Scales. Technical Report. University of Massachusetts, USA.

Skyrms, Brian. Signals: Evolution, Learning, and Information.. Oxford University Press, 2010.

As opposed to functions over sets in formal semantics.

People would literally hand-write rules in lambda calculus for concepts like “tallest” and “and”.

This would require engineering all the perception (e.g. classifiers for dogs, cats, colors, shapes, etc.) and action abstractions (e.g. skills for running, throwing, jumping, backflipping) and mapping language to those abstractions.

This is ameliorated somewhat by pre-training modality-specific encoders before merging them with supervision tuples.

These researchers are my personal heroes — if you know them, I would love an introduction!